McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819)

By Ethan Harris ‘27

Introduction

McCulloch v. Maryland, decided on March 6, 1819, was one of the first, if not the most influential, decisions to establish national power in the United States. The “Supremacy Clause” is a foundational principle of our government. The supremacy clause, which can be found in Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, established federal law as the “supreme Law of the Land.” The main issue in McCulloch v. Maryland was whether or not the federal government had the power to establish a national bank. If that were the case, then the court would additionally examine Maryland’s taxing laws, a law which was passed to oppose the national bank, and decide whether or not they were interfering with congressional powers.

Facts of the case

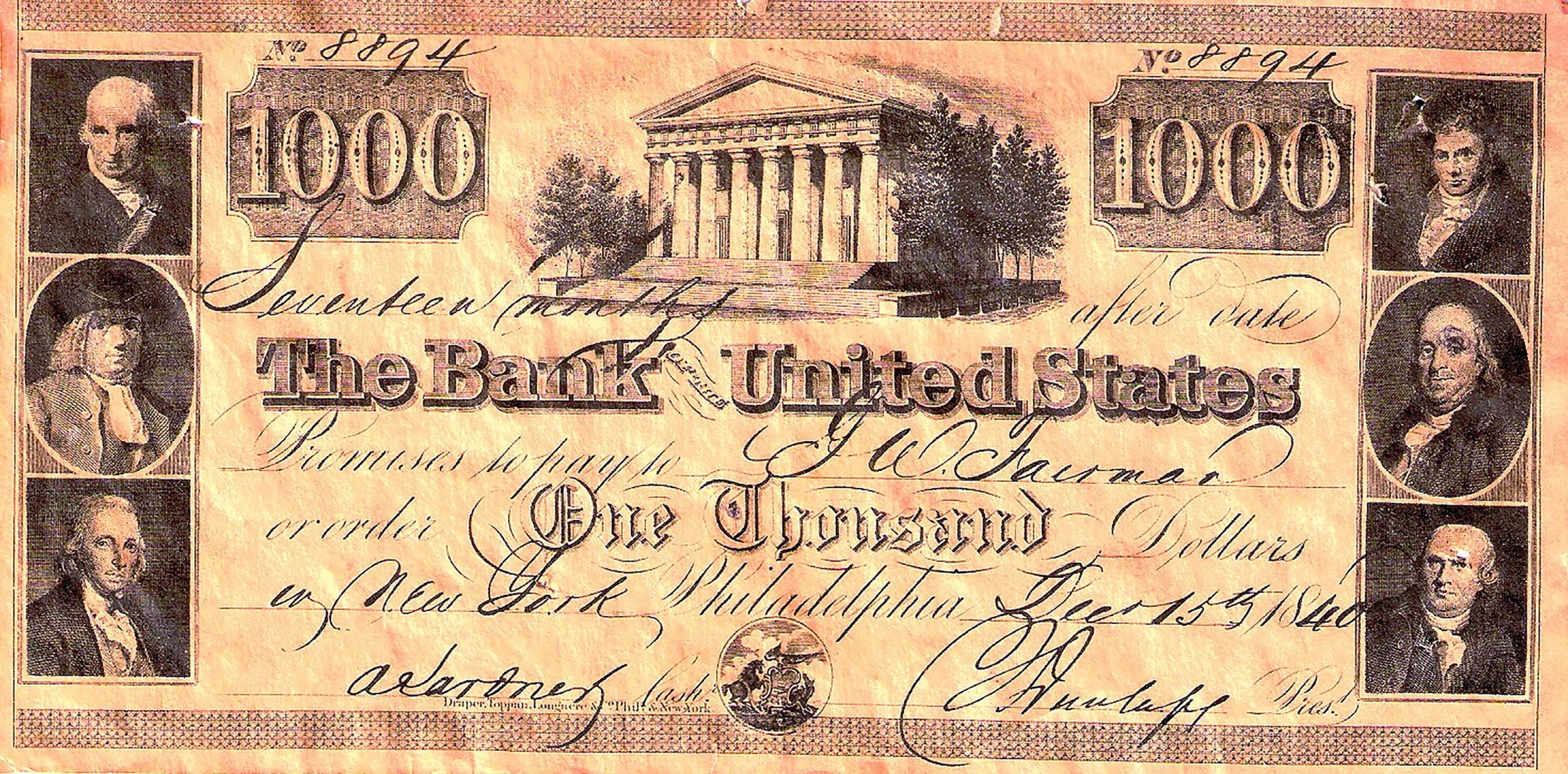

The United States federal government, specifically Congress, established the Second National Bank in 1816. The First National Bank was established in 1791, and although its twenty-year charter yielded positive results, the renewal of the bank was denied by just one vote in Congress. With the majority of Congress against another national bank and along with the mastermind behind the plan, Alexander Hamilton, having passed away, the vision of a national bank seemed to be fading. However, positions changed following the War of 1812. After three years of fighting with Britain over trading disputes, the United States was exhausted economically. Many state banks were failing to redeem their notes and fulfill contractual obligations. In 1815, James Madison, the then-president and a long-time opponent to the idea of a national bank, reluctantly agreed that the United States needed a uniform national bank to help reinvigorate the economy. After months of debate, Madison signed an act establishing the Second National Bank.

The Second National Bank indeed succeeded in its goal. Through both public and private leadership, along with a network of twenty-five branches spread throughout the country, the Second National Bank created a stronger and more stable economy. It also greatly aided westward expansion. The issues began with just one of the 25 branches, specifically the Baltimore, Maryland, branch. In 1818, the Maryland legislature passed a law requiring the Baltimore branch of the Second National Bank to pay a $15,000-a-year tax. Adjusted for inflation, this is well over $300,000 a year. The Baltimore branch wasn’t too happy about this new law, and a cashier by the name of James W. McCulloch refused to pay the tax. This refusal to follow Maryland state law resulted in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland.

Who was making the decision?

The United States Supreme Court had John Marshall as their chief justice at the time. Marshall, who had the longest tenure as chief justice, is well known for his court’s powerful and influential decisions. He is most famous for his 1803 decision in Marbury v. Madison, which established the power of judicial review. He is also known for drawing the line between federal and state power on multiple occasions, with McCulloch v. Maryland being a great example. Marshall was joined by justices Bushrod Washington, William Johnson, Henry Brockholst Livingston, Thomas Todd, Gabriel Duvall, and Joseph Story.

Constitutional issue

As mentioned before, the court had two questions to answer: Does Congress have the power to establish a national bank? If so, does Maryland have the power to tax the national bank under constitutional law? The answer to these questions can be found in the U.S. Constitution, or, rather, the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. The argument by Maryland was that “the power to establish a national bank” cannot be found anywhere in the Constitution. That is absolutely correct, and the lower courts sided with Maryland, arguing that the power Congress sought needed to be in written in the Constitution.

Clearly, the most relevant section of the Constitution for this case is Article I, Section 8. This section of the Constitution clearly outlines the powers of Congress. It mentions the power to regulate commerce, coin money, declare war, and much more. It does not mention the power to establish a national bank. However, the very last sentence in Article I, Section 8 opens the door to Congress’s power. It states Congress has the power “To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.” The necessary and proper clause, at first glance, allows Congress to essentially create any law it wants, as long as those laws are necessary, proper, and are created to execute the other federal powers granted in the Constitution.

Another piece of law relevant to this decision is Article VI. Paragraph two of Article VI tells us, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” The phrase “Laws of the United States” is the most important part. This section of the Constitution tells us that federal laws take precedence over any state laws.

John Marshall and the United States Supreme Court used these two sections of the Constitution to make their decision regarding McCulloch v. Maryland.

The decision

John Marshall and the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of McCulloch. The court decided not only did Congress have the power to establish a national bank, but also had no right to tax that bank’s branch in Baltimore. Marshall stated in the court’s opinion, “Although, among the enumerated powers of government, we do not find the word ‘bank,’ or ‘incorporation,’ we find the great powers to lay and collect taxes; to borrow money; to regulate commerce; to declare and conduct a war; and to raise and support armies and navies.” Marshall agrees with Maryland that the word “bank” isn’t included in the Constitution. However, Marshall found that the powers which are listed in the Constitution, along with Article VI, indeed meant Congress had the power to establish a national bank. Marshall redefined the necessary and proper clause. “Necessary and proper” would now mean “appropriate and legitimate”. Marshall stated, “The powers it confers are to be carried into execution, which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it, in the manner most beneficial to the people. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.”

Considering that Congress indeed had the right to establish a national bank, the court then had to ask the question of whether or not Maryland had the right to tax the national bank. Again, the court sided with McCulloch, as it found Maryland did not have that right. Their reasoning was simple: “That the power to tax involves the power to destroy.” The court argued that if Maryland was allowed to “destroy” the Baltimore branch of the Second National Bank, then it’d have the power to destroy all federal law contained within the borders of Maryland. The power of a state to completely override federal law goes against the foundation of the United States. Marshall said it best: “This was not intended by the American people. They did not design to make their government dependent on the states.”

Impact today

The clearest impact McCulloch v. Maryland had on the United States was the clear definition of the relationship between state and federal law. Specifically, the fact that when state and federal law are in conflict, federal law always wins. This case set a precedent that has been and will continue to be used throughout history. Cases like Gibbons v. Ogden, Worcester v. Georgia, and Albeman v. Booth all used the supremacy clause and the precedent of McCulloch v. Maryland to decide whether or not state laws were contradicting federal laws. This case will continue to be the foundation of decisions for every instance where a state law opposes a federal law.

Ethan Harris is a junior majoring in political science, criminal justice, and philosophy.

Sources

Legal Information Institute. Supremacy Clause. Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/supremacy_clause

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819)

Temme, L. (2022). McCulloch v. Maryland Case Summary. FindLaw. https://supreme.findlaw.com/supreme-court-insights/mcculloch-v--maryland-case-summary--what-you-need-to-know.html

The First Bank of United States. (2015). Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/first-bank-of-the-us#:~:text=President%20Washington%20signed%20the%20bill,with%20a%20twenty%2Dyear%20charter.

U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8.

U.S. Const. art. 6.