Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824)

By Avery Sneed ‘27

Introduction

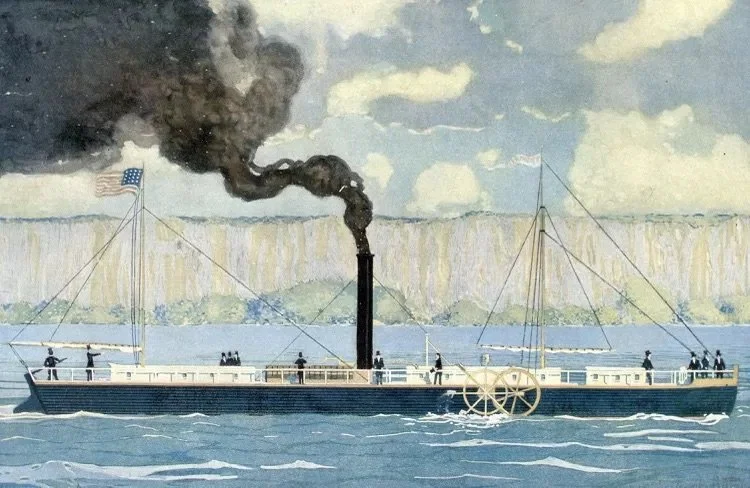

By the early 19th century, the young American nation was on the move—literally. As the Industrial Revolution took shape, commerce expanded at an unprecedented rate, and steamboats transformed rivers and coastlines into bustling highways of trade. These new economic corridors connected cities and states, allowing goods and people to travel farther and faster than ever before. However, with this expansion came disputes over control.

A fundamental question emerged: Could individual states grant exclusive navigation rights within their waters, or was that power reserved for the federal government? The stakes were high, as whoever controlled the waterways controlled commerce itself. The Supreme Court’s decision in Gibbons v. Ogden would settle this question, laying the foundation for how interstate commerce would be regulated in the United States for generations to come.

The Marshall Court

The case was decided by the Marshall Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall. The Marshall Court is widely regarded as one of the most transformative courts in American history, as its rulings significantly shaped the power of Congress, the role of the judiciary, and the relationship between state and federal governments.

Perhaps the Court’s most defining moment came in Marbury v. Madison (1803), when Marshall established the principle of judicial review, giving the Supreme Court the power to determine whether laws were constitutional. This decision solidified the Court’s role as the final interpreter of the Constitution and strengthened the judiciary against the legislative and executive branches.

In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Court took another major step in reinforcing federal power, ruling that Congress had implied powers under the Necessary and Proper Clause, and that states could not interfere with federal institutions. This federalist approach set the stage for Gibbons v. Ogden, where the Court once again ruled in favor of federal authority.

A Steamboat Showdown

The conflict in Gibbons v. Ogden was rooted in a failed business partnership, but its implications stretched far beyond a dispute between two men.

Before acquiring their monopoly on steamboat navigation in New York, Robert Livingston was a prominent American lawyer, founding father, and politician. He was a member of the Committee of Five who helped draft the Declaration of Independence, and later served as the U.S. Minister to France, where he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase. Robert Fulton was an inventor and engineer with a background in mechanics. While negotiating the Louisiana Purchase, Livingston met and became friends with Fulton, and the two entered a joint partnership. Their combined efforts led to the creation of the first operational steamboat, The North River Steamboat, which broke the record for the quickest voyage from New York City to Albany, New York. Because of their successes, the New York State Legislature granted Livingston and Fulton an exclusive navigation monopoly over New York’s waters for 20 years. This monopoly gave them complete control over commercial transportation in the state, allowing them to license operators at will.

In 1815, Aaron Ogden, a former New Jersey governor and Revolutionary War veteran, purchased a license from the Livingston-Fulton monopoly and began operating steamboats in New York. Shortly after, he entered into a business partnership with Thomas Gibbons, a businessman from Georgia, to run a joint ferry service between New York and New Jersey.

However, the partnership lasted only three years before things took a turn for the worse. Gibbons began running his own ferries along the same route, directly competing with Ogden’s business. Furious, Ogden sought an injunction from the New York state court, arguing that Gibbons was violating the exclusive rights granted to him by the state.

Gibbons, in his defense, pointed out that he had obtained a federal coasting license under the 1793 Licensing Act, a law passed by Congress regulating coastal trade. He argued that this federal authorization superseded New York’s monopoly.

The New York courts ruled in favor of Ogden, affirming the state's authority to regulate its own waters. After exhausting his legal options at the state level, Gibbons appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in 1824.

Who Controls the Waterways?

By the time Gibbons v. Ogden reached the Supreme Court, the United States had been wrestling with the balance of state and federal power for decades. The ideological divide between Federalists and Anti-Federalists had shaped American governance since the Constitution was ratified, and those tensions continued to influence the courts well into the 19th century. At the heart of Gibbons v. Ogden was a question that would define the future of commerce clause jurisprudence: Who has the power to regulate interstate commerce—the states or the federal government? Just five years after McCulloch v. Maryland, the Supreme Court was once again faced with a case that would test the limits of federal authority. The dispute between two steamboat operators was about more than just business—it was about defining the balance of power in a growing nation. The Court’s decision would carry far-reaching implications, shaping the framework of American commerce regulation for generations to come.

The Decision

In a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gibbons, significantly expanding federal power over commerce. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Marshall took a multi-tiered approach to interpreting the Commerce Clause, marking the first time the Court had directly defined its scope. The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, grants Congress the power “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” The Commerce Clause ensures that the federal government has authority over economic activity that crosses state lines, ensuring that states cannot enact laws that interfere with national trade.

In Gibbons vs. Ogden, Chief Justice John Marshall nullified New York’s steamboat monopoly, ruling that it conflicted with the 1793 Licensing Act, a federal law governing coastal trade. Since federal law is superior to state law, New York’s grant to Ogden was unconstitutional under the Supremacy Clause.

The court then took the opportunity to define “commerce.” Marshall defined it quite broadly, stating that the Commerce Clause not only encompasses exchange of goods, but also “intercourse” between states, which includes navigation. The Court also interpreted the phrase “among the several states”, explaining that “among” was akin to “intermingled with.” Essentially, this interpretation suggests that interstate commerce does not stop at a state’s border, but extends into a state so long as it affects trade between multiple states. This interpretation established that Congress’s authority to regulate interstate commerce was absolute.

Ultimately, the monopoly was invalidated and Ogden was allowed to continue his own ventures in New York’s laws. John Marshall’s ruling decisively strengthened the power of the federal government, simultaneously establishing the powers of the Commerce and Supremacy Clauses. Marshall’s opinion reaffirmed the fact that when federal and state laws clash, federal law prevails. In his opinion, he famously declared: “The act of Congress or the treaty is supreme; and the law of the state, though enacted in the exercise of powers not controverted, must yield to it.”

Impact

The decision in Gibbons vs. Ogden laid the foundation for Congressional regulation of intrastate commerce, as long as it directly impacts interstate commerce. This meant that Congress would now have preemptive authority over any commercial activity that takes place between state lines. As a result, any law passed by states that regulated in-state commercial activity could potentially be overturned if it was deemed to affect interstate commerce.

Gibbons has been cited as precedent for a number of landmark decisions that have expanded Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause. One of the most significant of these was the Court’s decision in Wickard vs. Filburn (1942), which upheld Congress’s authority to regulate a farmer’s wheat production despite not being involved in interstate commerce. The Court relied on the precedent set in Gibbons to conclude that the economic effect an activity has on interstate commerce is reason enough to determine that it can be regulated by Congress–despite its intrastate nature.

Relevance Today

The Supreme Court’s decision in Gibbons remains highly important today, as it lays out Congress’s authority to regulate interstate commerce, a power that continues to invoke economic and legal debates. The ruling establishes that the federal government has the ultimate authority to regulate commerce that crosses state lines, preventing individual states from enacting laws that conflict with national economic policy interests. This principle has been reinforced time and again, granting the government authority to regulate a wide array of industries from transportation to healthcare.

However, more recent Supreme Court rulings, such as in United States vs. Lopez (1995) and National Federation of Independent Business vs. Sebelius (2012), have begun to restrict Congress’s broad authority under the Commerce Clause. These rulings have established that while Gibbons still remains the basis for Congressional regulatory power, there are still judicially recognized boundaries between what is proper and what is overreach. The ongoing evolution of Commerce Clause jurisprudence highlights the lasting impact of the decision in Gibbons vs Ogden as a foundational case that continues to guide the balance of power between federal and state regulation in the modern economy.

Avery Sneed is a sophomore majoring in political science.

Sources

Cornell Law School. (2022, January). Legal Information Institute. Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/gibbons_v_ogden_(1824)#:~:text=Primary%20tabs-,Gibbons%20v.,interstate%20and%20some%20intrastate%20commerce.

Justia. (n.d.). Justia: U.S. Supreme Court. John Marshall Court (1801-1835). https://supreme.justia.com/supreme-court-history/marshall-court/

McBride, A. (2007). Landmark Cases: Gibbons vs Ogden (1824). PBS: Thirteen. https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_gibbons.html

Minnesota Judicial Training & Education Blog. (2022, August 1). Minnesota Judicial Training & Education Blog. United States Supreme Court Series: 45 of the most significant decisions (2 of 45 – Gibbons v. Ogden). https://pendletonupdates.com/2022/08/01/united-states-supreme-court-series-45-of-the-most-significant-decisions-2-of-45-gibbons-v-ogden/

Quimbee. (2007, December 15). American Bar Association. These two dudes owned some steamboats, their suit did SCOTUS quell (Gibbons v. Ogden). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_students/resources/on-demand/quimbee-gibbons-v-ogden/

Sobel, R., & Raimo, J. (n.d.). National Governors Association. Gov. Aaron Ogden. https://www.nga.org/governor/aaron-ogden/

Supreme Court Historical Society. (n.d.). History of the Courts. The Marshall Court, 1801-1835. https://supremecourthistory.org/history-of-the-courts/the-marshall-court-1801-1835/

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1 (1824) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/casefinder.aspx

United States v. Lopez, 514 U. S. 549 (1995) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/casefinder.aspx

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. 111 (1942) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/casefinder.aspx

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U. S. 519 (2012) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/casefinder.aspx

Historical Society of the New York Courts. (n.d.). Historical Society of the New York Courts. Robert R. Livingston. https://history.nycourts.gov/figure/robert-r-livingston/

Britannica. (1998, July 20). Britannica: Science and Tech. Robert Fulton. Retrieved April 1, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Fulton-American-inventor