17th Century Witchcraft Laws in The American Colonies

By Olivia Marcoccia ‘28

Today, it is hard to rationalize the 17th-century witch trials because the American legal system has operated with due process for almost two hundred years. “Due process” encompasses many aspects of the judicial system, such as procedural action and constitutional rights, but broadly, it guarantees a fair trial. Way before the Bill of Rights introduced due process, the American Colonies were under British control. Each colony had differing laws, but most took inspiration from British statutes.

Three years before the first American colony was established, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act of 1604. This wasn't England's first attempt at outlawing witchcraft, but it was the most impactful. The act was more inclusive than its predecessors, meaning that it added more regulations and definitions to "witchcraft". Specifically, the act outlined that anyone who "conjures, invokes, or consults with a wicked spirit", takes any person from their grave, interacts with a "familiar" (an animal such as livestock, cats, or mice), or uses an “enchantment, a charm, or sorcery” will be subject to conviction. A first witchcraft conviction could lead to a maximum of one year in prison and was considered a felony. A second conviction was less forgiving; two-time witchcraft offenders were sentenced to death. The act was meant to protect the public from injuries and harm, similar to the broader outlawing of battery or homicide that we have today.

Legally, that all makes sense. Logically, there were some problems. Proving witchcraft, in 1604, was difficult for obvious reasons. As a result, not many people were sentenced to death under this law. For instance, a 1626 case shows that Joan Wright, from the Virginia colony, was tried for witchcraft and admitted to the claims but was ultimately acquitted because the case did not have "irrefutable evidence" to support her conviction. In fact, Virginia tried more defamation-like lawsuits regarding witchcraft accusations than actual witchcraft trials. This led to the 1655 law that made it a crime to falsely accuse someone of witchcraft. Punishments for violating this law included a fine of one thousand pounds of tobacco and possible imprisonment. Overall, Virginia was not receptive to the witchcraft mania because of the hefty burden of irrefutable evidence that its courts mandated.

Other colonies took harsher measures against witchcraft and aired on the side of caution rather than reason. In Connecticut, twelve crimes were punishable by death. Witchcraft became one of them in 1642. Similarly, the Massachusetts Bay colony's legislative body, the General Court, included witchcraft in its list of crimes and laws (a document called The Body of Liberties). The law was as follows: “If any man or woman be a witch, that is, hath or consulteth with a familiar spirit (a devil or demon that aided the witch to perform bad deeds through magic), they shall be put to death." This austere law provided the groundwork for the religious paranoia that would ultimately lead to the imprisonment of over a hundred people and the execution of twenty during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

Before 1692, however, people were often not executed for witchcraft. Juries still relied on the English Common Law principle of requiring clear and convincing evidence. For the Massachusetts colonists, this meant an admission of guilt and accusations from two trustworthy people. The colony continued as normal until 1684, when its charter was temporarily suspended for violating Britain's Navigation Act. As a result, Massachusetts Bay became a royal colony and lost most of its authority over itself (including the laws outlined in the Body of Liberties). England had direct control over the colony until it regained its charter in 1691. At the time of the new governor's arrival, the colony did not have any established laws. This is what set the Salem Witch Trials apart from the previous cases. The governor, William Phips, created the Court of Oyer (hear) and Terminer (determine) as one of his first actions.

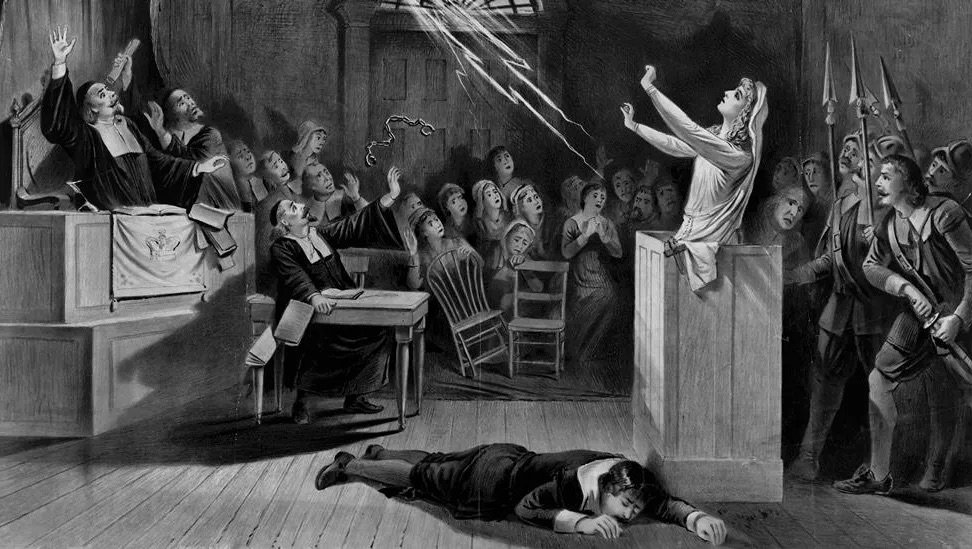

Without any official laws, judges relied on spectral evidence and rarely anything else. This meant that anyone could claim that someone visited them in their dreams as a witch, performed witchcraft in front of them, interacted with wicked spirits, etc. Records show that the judges weren't impartial either, adding to the unjust system. "The two magistrates conducted their examination more like prosecuting attorneys than impartial investigators," one scholar notes. Courts also considered "bodily marks" as evidence of being connected to the devil. Prior to the trials, but after being accused, "witch tests" would sometimes take place. This included throwing a person into a body of water to see if they sank. Sinking meant that the person was not a witch, but floating could lead to execution since these tests were used as solid evidence in the trials. Unlike today, defendants were not given a lawyer. On the bright side, they could accuse someone else of witchcraft to get out of their charges. This caused accusations to spread like wildfire. Since people who questioned the merits of the trial or convictions were usually accused as well, there wasn't a way to put out the fire. The accused were put in prison to await trial and tortured to falsely admit guilt if other forms of evidence didn't exist. This lawless judicial system went on for four months until the then-president of Harvard shared his concerns about spectral evidence: "It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned."

Governor Phips dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer. The remaining witchcraft cases were heard in the newly established Superior Court of Judicature. With spectral evidence now inadmissible, most of the trials ended in acquittal. Eventually, Phips pardoned the remaining prisoners. The colony composed itself as the witch trials ended. Forty-three years later, the Witchcraft Act of 1604 was repealed.

Reflecting on the Salem Witch Trials invokes a new appreciation for due process, burdens such as "beyond a reasonable doubt" and "by the preponderance of the evidence", and the modern-day rules of evidence.

Sources

Berkshire Law Library. (2017). Witchcraft Law up to the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Mass.gov. https://www.mass.gov/news/witchcraft-law-up-to-the-salem-witchcraft-trials-of-1692

Billings, W. & Manning, K. (2022). Salem Witchcraft Trials. Ebsco.com. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/salem-witchcraft-trials

Parliament. (1604). An Acte against Conjuration Witchcrafte and dealing with evill and wicked Spirits. Encyclopediavirgina.com. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/an-acte-against-conjuration-witchcrafte-and-dealing-with-evill-and-wicked-spirits-1604/

Purdy, E. (2024). Salem Witch Trials. Firstamendment.mtsu.edu. https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/salem-witch-trials/

Sheposh, R. (2022). Witchcraft in Colonial America. Ebsco.com https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/witchcraft-colonial-america